GUEST POST: SO MANY ALTERNATIVES: What Do I Do…? Take a Deep Breath — There’s No Rush

Overview:

- FOMO (fear of missing out) is driving many financial advisors to feel rushed into alternative investments, fueled by private markets’ aggressive marketing push to attract new capital from the Private Wealth channel.

- Investing in alternatives is a long-term strategy that requires discipline, thorough manager due diligence, and a patient approach.

- Market data[1] shows no correlation between valuations and short-term returns, but a strong inverse relationship between valuations and long-term performance.

- Surging fundraising in private markets may signal peak-cycle enthusiasm and should not automatically be interpreted as an indicator of future outperformance.

- Exceptional managers maintain valuation discipline, recognize when sectors become overcrowded, and adapt strategies accordingly across market environments.

- When initially allocating to private markets, manager selection outweighs market timing concerns; the best managers navigate rather than attempt to time market cycles, providing protection against bubbles.

FOMO and the Rush to Private Markets

For many financial advisors and investors not purely focused on portfolio management, the sheer volume of marketing pitches, financial headlines, LinkedIn posts, and industry narratives surrounding private investments has created an intense sense of urgency. As with many “new things,” some fear missing out on a fast-moving trend, while others worry that not understanding these strategies could put them at a competitive disadvantage.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. But in most cases, the pressure to move quickly is actually a signal to slow down. Investing in alternatives is a long-term strategy, and unless you are a high-risk-tolerance venture capital investor, it’s not about being first — it’s about doing it right. That means focusing on:

- Financial advisory discipline;

- Manager due diligence and selection; and

- A patient, measured approach.

If you get the first two right and can maintain the third, you’re on solid ground. Many advisors feel pressured to allocate to alternatives because they fear falling behind. But when investors act on urgency rather than strategy, capital tends to flow indiscriminately. This is how bubbles form — not through individual bad investments, but through collective overconfidence and price-insensitive capital allocation. History is full of examples where market enthusiasm led to distorted valuations. Howard Marks’ recent memo “On Bubble Watch” (January 7, 2025) offers a timely reminder of why chasing hot sectors without regard for price has rarely ended well. In the memo, Marks highlights how bubbles are fueled more by psychology than fundamentals — capital often flows not because of deep opportunity, but because of momentum, optimism, and fear of missing out. Alternative investments are no exception — when a strategy becomes overcrowded, return potential can be eroded.

Chasing Returns, Capital Flows, and Bubbles

I’ve wanted to write this piece for some time but hesitated because I wasn’t sure I had what I was looking for to articulate what I’ve seen play out over multiple investment cycles. The patterns of capital flows, bubbles, and late-stage investment traps repeat across decades.

I vividly remember the dot-com bubble. During my high school internship at a brokerage firm, I was trading internet stocks with money I had earned from refereeing soccer games and delivering newspapers. The head of the branch told me daily that this was a bubble, just like the casino stocks of the ‘70s. I dismissed him — after all, this time was different, right? The internet was going to change everything.

Well, it did change a lot. But when the bubble burst, I lost every penny of my gains after doubling down on fiber-optic stocks, convinced they were critical to the infrastructure spend of the future. Corning, now widely recognized for its Gorilla Glass protecting billions of smartphones and its essential fiber optic technology, has still never recaptured its dot-com era stock price highs — a sobering reminder that even when you’re right about a technology’s importance, timing and valuation remain critical.

There have always been a couple of commentaries I consistently look forward to reading. The late Byron Wien’s “10 Surprises” was one I found particularly insightful, and Howard Marks’ Memos are another I continue to enjoy. In “On Bubble Watch“, Marks discusses how investors often convince themselves that “this time is different,” ignoring historical parallels and the risks of inflated valuations.

Marks highlights a few investment realities that should always be kept in mind:

- “It’s not what you buy — it’s what you pay that counts.” Investors often focus on the quality of an asset without considering whether its price already reflects all potential upside.

- “Good investing doesn’t come from buying good things, but from buying things well.” Even strong companies or sectors can deliver poor returns if acquired at excessive valuations.

- “There’s no asset so good that it can’t become overpriced and thus dangerous, and there are few assets so bad that they can’t get cheap enough to be a bargain.” Every asset, no matter how promising, has a point at which future returns become inadequate or negative due to overvaluation.

These principles act as guardrails to prevent getting caught up in speculative frenzies. Investors who ignore them often find themselves chasing momentum rather than value — an all-too-common pitfall in alternative investments today. The best alternative investment managers embody these principles, demonstrating restraint when others are greedy and the courage to deploy capital when others retreat.

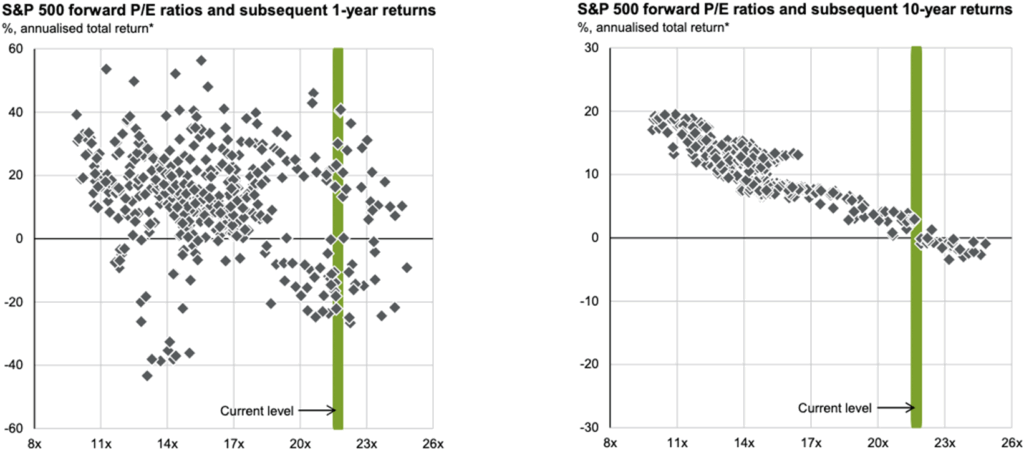

The charts below, particularly the one on the right noted by Marks, powerfully illustrate why timing and patience are important in making investment decisions.

The left chart shows 1-year returns plotted against S&P 500 P/E ratios, revealing significant scatter with no predictable pattern — high valuations can lead to both gains and losses in the short term. This unpredictability mirrors the danger of chasing today’s “hot” alternative investments based on recent performance or fundraising headlines.

The right chart, however, shows the clear inverse relationship between S&P 500 P/E multiples and 10-year annualized returns. Higher valuations consistently result in lower long-term returns — a reality that becomes inescapable over time. For alternative investments with typical 3-7 year realization periods, this principle is especially relevant. The capital rushing into alternatives today, based on FOMO, may experience the disappointing outcomes shown on the right side of this chart when those investments are realized years later. This data reinforces the central argument: alternatives require patience and discipline, not urgency, as today’s “must-have” investment may well become tomorrow’s overcrowded, underperforming asset class.

Source: JPMorgan Asset Management, Market Insights: Guide to the Markets UK | Q1 2025.

Rather than trying to time cycles or chase trends, focusing on selecting the right managers ensures you are positioned for long-term success, regardless of where we are in the capital cycle. Bubbles shouldn’t make you sit on the sidelines — they should inform your return expectations. Valuation discipline is important, but well-chosen managers can effectively deploy capital in any cycle.

Capital Flows and Being Late to the Party — A Costly Mistake

This pattern of over-exuberance isn’t limited to public markets. In private markets, we see a similar effect — investors not wanting to be left out of ‘hot’ sectors can often allocate capital at the tail-end of opportunities, which can turn out to be the wrong time. Fundraising growth often serves as a psychological anchor for investors — many assume that because capital is flowing, they must follow. But history shows that when capital floods a strategy, future returns tend to diminish as more capital is chasing the same returns. The very same fundraising data used to justify an investment might actually indicate that the best opportunities have already passed.

The relationship between capital growth in a sector and the future return potential has been widely studied. The more capital that floods a space, the harder it is to generate excess returns.

- The first movers capture the best deals.

- The second wave fights for scraps — but can sometimes learn from the early entrants.

- Those who arrive later often overpay — leading to diminished returns or outright losses.

Private markets, being opaque by nature, provide little real-time data to assess these cycles. The one metric that gets the most attention is fundraising data — how much capital was raised, year-over-year growth, the sector’s CAGR, etc. While these statistics may be interesting, they are not predictive of returns.

So what if capital raised is up 30% year-over-year?

- Does it mean higher returns? No.

- Does it mean better investment opportunities? Not necessarily.

- Does it often mean certain opportunities have already been crowded out? It’s complicated.

Capital flow trends require context — a single year’s increase may be the beginning of a multi-year growth trend, or it might signal late-stage saturation. While some market expansions are justified by structural shifts — such as post-GFC private credit growth — many cycles have ended with capital chasing diminishing returns. Some sectors can absorb increasing capital for several years before showing signs of overcrowding, while others become competitive much faster. There’s no universal threshold or metric that definitively signals when a strategy has

become overcrowded. The impact depends on several factors: the starting size of the market, its growth potential (including unforeseen applications, as seen in SaaS markets that expanded

far beyond initial expectations), barriers to entry, and how quickly new entrants can scale their participation.

Since we can’t predict when capital flows into a particular sector will peak, the best defense against bubbles isn’t timing — it’s selecting managers with the discipline to invest wisely in any environment. Exceptional managers recognize when a sector is becoming overcrowded and adapt their strategies accordingly, sometimes by adjusting their investment pacing, demonstrating purchase price discipline to the point of passing on overvalued opportunities, or shifting to less trafficked segments of the market. Even these exceptional managers may face headwinds during extreme bubble environments, but their discipline and adaptability allow them to minimize drawdowns/capital calls and position for the eventual recovery, often by maintaining higher cash reserves/uncalled capital or focusing on less cyclical opportunities.

That said, it’s important to recognize that even the most disciplined managers cannot fully escape systemic risks during extreme market dislocations. When bubbles burst, correlation across investments tends to increase, and even carefully selected managers may experience significant valuation declines or impairments to portfolio companies. The advantage of superior manager selection isn’t complete immunity from market cycles — it’s better relative performance through the cycle, smaller losses to NAV, and potentially faster recovery compared to less disciplined peers. Manager selection reduces but cannot eliminate the impact of broad market bubbles.

There is no crystal ball to determine when too much capital becomes excessive, but ever-increasing fund sizes, along with valuations, may serve as a canary in the coal mine. Investors should remember: asset managers typically receive a large portion of their compensation from AUM (assets under management), and while some impose hard caps, it’s never easy to turn away capital. This is where experienced voices can provide critical perspective.

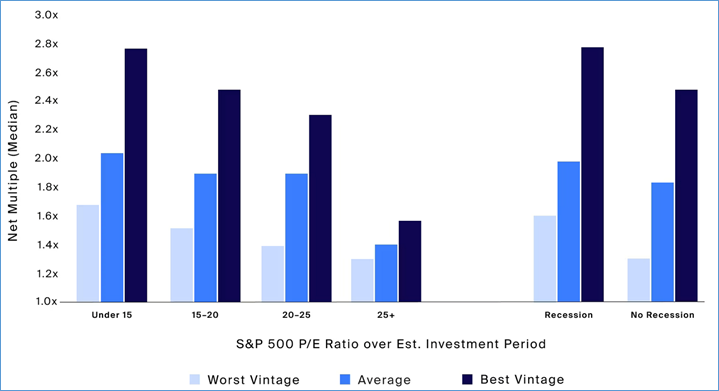

The chart below highlights how private equity funds initiated during periods of high valuations tend to underperform those launched in lower-valuation environments. Even recession-era vintages often outperform those initiated in peak-cycle periods, reinforcing the importance of timing and discipline in manager selection.

Source: CAIS. The Importance of Entry Point for Private Equity Vintage Performance. S&P 500 Average P/E over Est. Investment Period represented by the average of the Price to Earnings Ratio of the SPX Index over years 0-3 of the vintage year, recession periods determined by USRINDEX Index, Preqin, Net Multiple (Median) by the Preqin Private Equity-All vintage year benchmark Median Net Multiple as of 7/31/2022. https://www.caisgroup.com/articles/the-importance-of-entry-point-for-private-equity-vintage-performance

A Disciplined Approach Wins in the Long Run

The key takeaway for investors and financial advisors who are new to private markets: alternatives can provide compelling returns, but only if approached with patience, purpose, and discipline.

Best practices for avoiding FOMO-driven investing:

- Ignore the noise. Just because capital is flowing doesn’t mean you need to follow.

- Do your diligence. The best opportunities require work — not just a marketing pitch.

- Understand cycles. Today’s most popular strategies may already be fully priced in.

- Be selective. First movers and exceptionally skilled managers tend to capture the best alpha, while late entrants more often take the leftovers.

If you’re investing today, you won’t realize the full return for three to seven years — or longer depending on market cycles. While understanding the cycle helps set appropriate expectations, manager selection remains the critical factor. The best managers demonstrate valuation discipline and the skill to identify opportunities across different market environments. They have the self-awareness to avoid overpaying, even when capital is abundant, and the patience to wait for attractive entry points. These qualities enable relative outperformance even during challenging periods. By prioritizing these manager attributes over simply chasing the latest trend, you position yourself for long-term success in alternatives. As always, the best decisions in alternatives aren’t made out of urgency — they’re made with patience and diligence. The best managers don’t time markets — they navigate them. Find them, and let them do

[1] Source: JPMorgan Asset Management, Market Insights: Guide to the Markets UK | Q1 2025.