PRIVATE MARKETS TODAY: Eyes Wide Open

Overview:

- Semi-liquid vehicles such as interval and tender offer funds have expanded access to private markets, supported by a growing interest in serving private wealth and retirement accounts and enabled by digital platforms that streamline administration.

- These structures offer meaningful investor benefits – immediate capital deployment, reduced administrative burdens, periodic liquidity – but also change how strategies fit and how returns are delivered.

- Some strategies are inherently a better fit for these structures than others, depending on how liquidity, valuation, and incentive alignment are managed.

- As more capital has entered the space, return expectations have evolved. Manager selection now plays an even larger role in outcomes.

- It is likely only a matter of time before we see funds that fully blend private credit and equity strategies within a single sponsor wrapper; these would bring new opportunities for portfolio design, alongside added structural considerations.

- With product structures evolving, investors need to focus not just on access, but on how the vehicle operates, how the manager invests, and whether the incentives are aligned.

Private Markets – Always Evolving

Private market vehicles have been around for decades. Until more recently, they had primarily been the domain of large institutions – pensions, endowments, insurers – and ultra-high-net-worth families. These groups manage long-term capital and have the resources to deal with illiquid structures and complex fund terms. As defined benefit plans gave way to defined contribution accounts, the profile of long-term capital started to shift and asset managers began looking for new ways to raise capital.

With over $31.6 trillion[1] globally (and growing) private wealth and retirement accounts represented a natural next frontier. But historically, administrative complexity, liquidity, and regulation kept the capital pool out of reach for asset managers and kept private market opportunities out of the hands of a much larger group of investors. It took time, but thanks to digitization and platform integration, it’s now possible to reach individual investors efficiently, resulting in new opportunities.

Assets in private markets have grown sharply – from $5.2 trillion in 2014 to $15.5 trillion in 2024[2]. Semi-liquid structures like interval and tender offer funds went from AUM of $34 billion in 2014 to over $170 billion[3] today. This growth reflects not just the capital raised, but the number of strategies being adapted to reach a broader base of investors.

For now, the bulk of capital is still in drawdown vehicles – 3(c)(7) funds with capital calls (also referred to as Qualified Purchaser or “QP” funds due to the investor restrictions) – but evergreen structures are gaining in popularity. While extremely early in the cycle of private wealth introduction and education, this growing accessibility and adoption could be viewed as where ETFs were in the early 2000s – adoption underway, credibility/acceptance growing, RIAs are taking them seriously, and product innovation is accelerating. They offer flexibility for investors who want to access private markets but are unable to, or do not want to, commit to a 7–10-year lockup. And they simplify ease of use while reducing the overall operational burdens that made private markets more difficult to access in the first place.

That said, the new structures are different. There’s no J-curve, you can put money to work right away, and you might even get liquidity – but the trade-offs are real. For investors used to traditional private markets, that difference matters.

Changing Structures

It is with these advertised benefits that investors need to go in with eyes wide open. These are not the same private market vehicles we read about during the rise of the Yale endowment model. Liquidity changes things, not always in predictable ways, and makes investments feel far more interchangeable and commodity-like.

Liquidity

With underlying asset liquidity being the main point of friction, some strategies fit the interval fund structure better than others, while tender offer funds may be more appropriate for less liquid assets. Private credit works well in an interval fund, as it is often short in duration, self-liquidating, and easier to manage inside a semi-liquid wrapper. Core and core-plus real estate can also work, as income is relatively stable and valuations can be more visible. Essential infrastructure offers yield as well, but the underlying assets are not exactly as liquid as a fully leased office building – how fast can you sell a bridge or transmission lines? Infrastructure may still fit, but it could benefit from the added flexibility of a tender offer structure. Private equity

secondaries can work too, but liquidity should be tightly controlled. Without consistent distributions or inflows, an interval structure can become stressed, especially in an environment with few exit options for the underlying investments. Even though portfolios may be mature and J-curve risk is reduced, equity is still equity, and gains remain unrealized until an exit occurs.

Returns

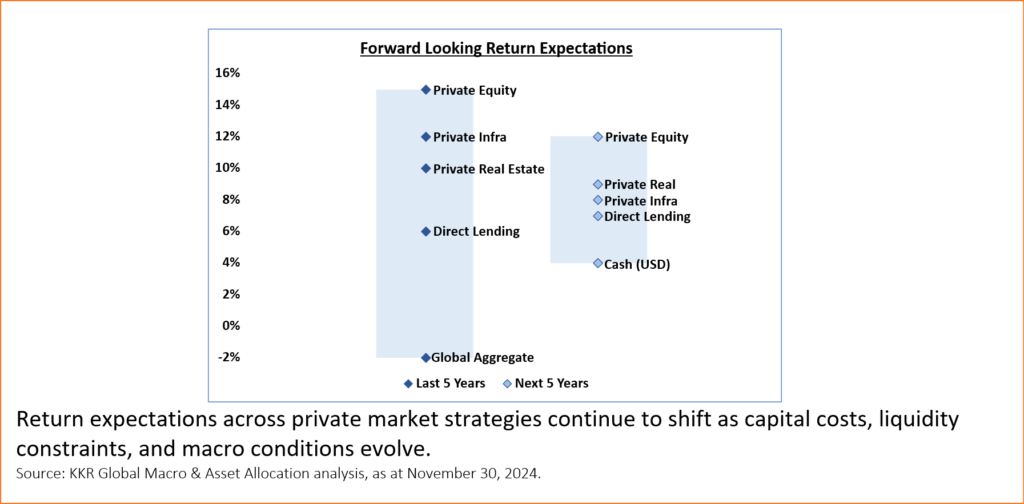

Return expectations have also shifted. Structures that remove friction and reduce certain risks, like evergreen formats, may also limit upside. Expectations should be lower than what many closed-end QP funds delivered in the past. Liquidity is available, but never guaranteed, and gates can be imposed in periods of stress. This is not always obvious in the way these funds are marketed.

The largest managers can often sound similar in what is offered, but not all of them create value the same way. That makes manager selection even more important. In a market where return dispersion is narrowing and product design is getting more flexible, understanding how a manager actually drives returns matters more than ever.

Shifts in capital markets have changed the equation for companies as well. Borrowers now have more options. They can fund growth, refinance, or expand using private credit, preferred equity, or private equity, depending on their needs and resources. That shift has also changed what investors are underwriting for and how they think about liquidity, risk, and expected return.

Private equity has faced the most pressure, with elevated valuations, fewer exits, and slower M&A activity weighing on performance. Private credit, by contrast, has seen strong inflows as investors seek yield and deal activity remains steady. For other strategies, return outcomes now depend on how critical leverage is to the model and whether that leverage is still available on attractive terms.

What’s Next: A Hybrid Frontier?

With the market evolving and asset managers continuing to build around semi-liquid formats, it is only a matter of time before we see vehicles that fully blend both private equity and private credit strategies into a single, long-term focused offering. This would go beyond the “across the capital structure” exposure touted by individual credit-focused funds with warrants, slivers of equity, or co-investment, and instead directly target both lending and equity buyout opportunities from the same sponsor, with both serving as core parts of the strategy, combining consistent contractual income with significant equity exposure through direct investing.

Structured properly, a single sponsor could create long-term vehicles that offer both yield and growth, a potential fit for retirement accounts with steady contributions and long horizons. The mechanics, both legal and operational, are no doubt being worked through by asset managers and regulators, but possible formats could include Target Date-like structures or a modified version of the European Long Term Investment Fund 2.0 (ELTIF 2.0). One of the most critical challenges will be structuring for and managing liquidity.

Groups like KKR, Blackstone, Ares, and Blue Owl already deploy both debt and equity across platforms, sometimes into the same deal, but usually through separate funds. What has not yet emerged at scale are vehicles designed from inception to allocate capital across the full balance sheet – not just shift within credit, but actively deploy into senior debt, preferred equity, and common equity buyouts under a single “capital solutions” mandate.

Conflicts, Incentives & Portfolio Design

That type of approach can also introduce conflicts. When both debt and equity sleeves are managed within the same firm, there may be less incentive to shop the deal or push for the best terms. In some cases, a manager might accept economics they normally would not, simply because the firm benefits from keeping the deal under the same roof.

These vehicles are also being developed in an environment where compensation is less tied to performance. In the absence of carry, there is a risk that priorities shift toward AUM growth and deal volume rather than generating long-term results. That may work for the firm, but it creates a layer of misalignment that investors need to be aware of.

If structured to maximize the investors’ experience – from returns, to education, reporting, and administration – these products could force a rethink of traditional portfolio construction.

Investors should be ready to move beyond 60/40 and take a total portfolio view – not just of allocation, but of how value is created and how capital is actually deployed. These are not securities you trade. They are assets you underwrite, and, if structured well, they can support long-term compounded growth through a blended, diversified return stream.

Expanded Access, More Homework

On the whole, the expansion of access to private markets should be welcomed, but only if investors understand what today’s private market vehicles offer. These are not the same funds that defined the early years of the endowment model. They may still provide diversification, lower volatility, and low correlation to public markets, but the return premiums are not the same.

Access is less of an issue today than it was a decade ago. The real work lies in understanding the structures, identifying where value is actually created, and avoiding the temptation to treat private markets as completely interchangeable with traditional asset classes. Manager selection matters and drives outcomes.

These vehicles are likely to play an increasing role in building long-term, diversified portfolios for all investors. But just like any other investment, investors still need to diversify thoughtfully, ensure the risk taken is understood, and matches the return being offered.

[1] Thinking Ahead Institute, Global Pension Assets Study 2025.

[2] PitchBook, values estimated from chart data in “2024 Annual Global Private Market Fundraising Report” (March 24, 2025)

[3] 2014 data ($34.3 billion as of 12/31/2014) from UMB and FUSE Research Network, “Unlisted CEFs: Proven Concepts Ready for Next-Generation Investors and Product Trailblazers” (2024); 2024 data ($172 billion as of 12/31/2024) from XA Investments LLC, “Non-Listed Closed-End Funds Fourth Quarter 2024 Market Update” (January 23, 2025).